I've been reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot (Picador, 2010). I knew about tissue culture and HeLa cells from my studies, so I skimmed through the beginning . The story took off for me once we reached the time when Deborah and Rebecca are researching the past together, the description of the difficulties arising from their own limitations and anxieties, and the way they resolved them. It carries the tone of truth-telling which makes the story speak to you from the page. Rivetting.

What impressed me most about this book is how painstaking Rebecca Skloot has been - careful to do justice to everyone who has contributed, the utmost care! This book has the longest list of acknowledgements that I have ever seen: it is a chapter in its own right, and it is well written too, I read it with great interest and a steadily increasing respect for the author. There is a proper index, a must for a book in this genre, but still, not everyone takes the trouble.There are the Notes, which provide the sources for each chapter. And the years in which the story takes place are written in a little stream at the head of each chapter with an arrow pointing to the relevant period .Very meticulous (unnecessary, to my mind, I read the book without any difficulty re the chronology and only noticed this feature later on.) There is also an Afterword which fills us in on the latest developments.

And yet it has not prevented the attacks: I read one vicious review which said that there was far too much of her in the book...Because she did the work without which no one would know what happened, the course of that work is the story, the story of how she managed to convince Deborah and the family to trust her, at some emotional cost to herself. Not an easy path, requiring great perseverance. She has done a good job of it, with considerable integrity.

This book brought me an unexpected gift: it has put me in touch with theory about structure. I have been worried about the structure of my book for some time and when I looked at Rebecca's website rebeccaskloot.com, I found that she said this about structure in an interview for the nieman storyboard:

" I knew that the structure was going to have to be complicated, and I’m just very into structure. I think structure is one of the most important tools a writer has. When I teach, my students get so sick of me harping on structure, structure, structure. I read and dissect a lot of things. I teach John McPhee’s stuff because he uses these very complicated structures you can pull apart. Structure is all about making the story more rich."

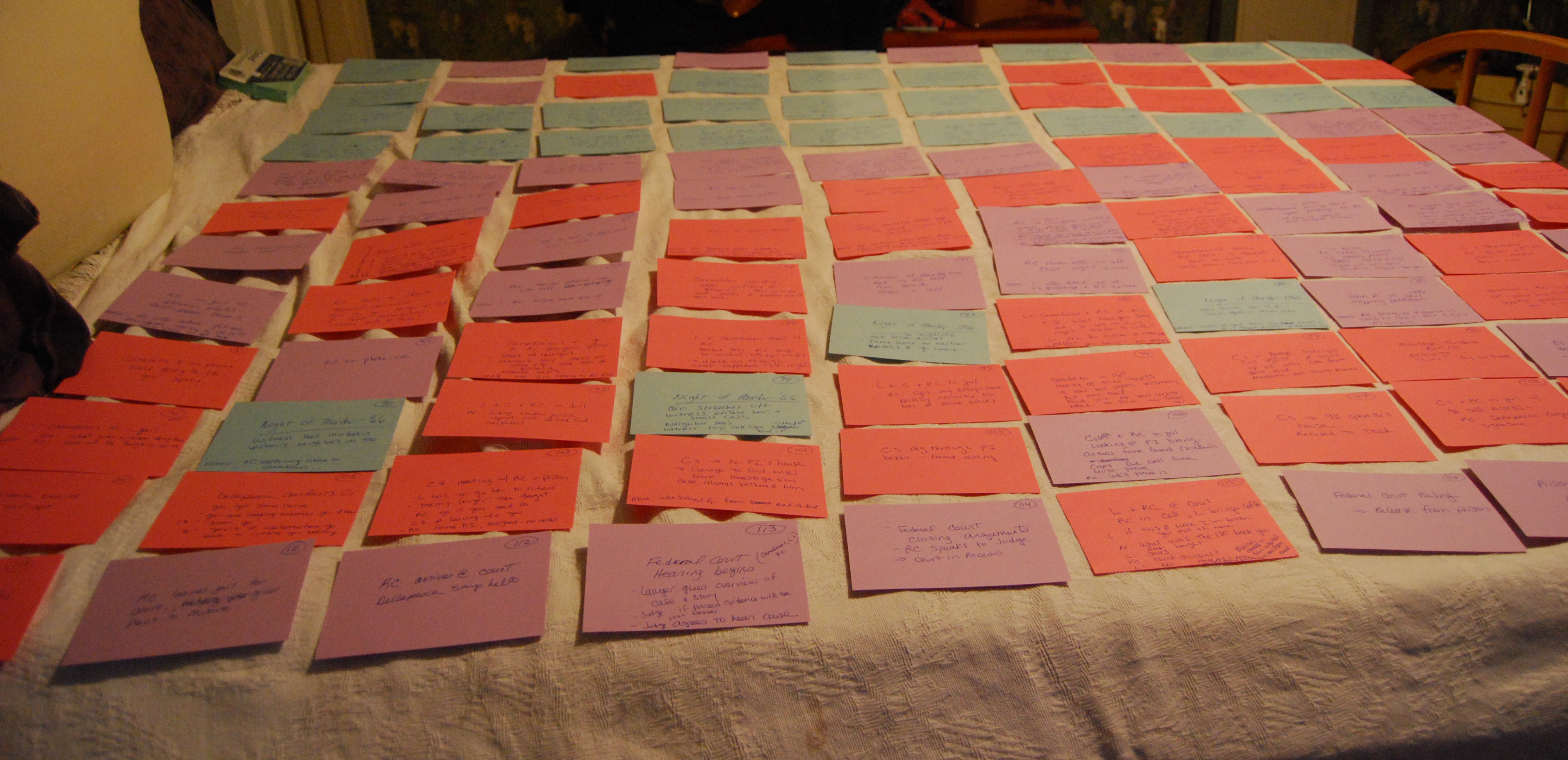

Here's a photo of the way she sorted out the structure: three interwoven stories, three colours. I was touched by this photo because I recognised it: I have done the same thing on our large dining table for my book, using colours for the four different interwoven stories and I did that because the structure was wrong and I was stuck. I recently found a way getting around some of the difficulties, involving, you guessed it, flashbacks. The issue now is - how to place them judiciously.

So on to "John McPhee's stuff". Here is a quote from the first article I found about him:

“...The narrative wants to move from point to point through time, while topics that have arisen now and again across someone’s life cry out to be collected..."The method is indicated for non-fiction writing, and mine is a mix of fiction and non-fiction - knowing more can only help! Some people advising me are writers of fiction, and they do not feel the same way about sticking to the facts when dealing with historical events. I have been told: "Readers will forgive you!" I don't want to have to be forgiven....

I also would like to mention that I have been encouraged to read how long it took Rebecca to write this book. Not that anything is likely to stop me at this stage.